Children are Not Props: Consent in the Global South

by

Anne Nwakalor, February 2023

by

Anne Nwakalor, February 2023

Consent is a buzzword within the global photography industry, which can be both positive and negative. Its positivity springs from its ability to reach many people, thereby educating and encouraging them to learn and unlearn. The negativity comes from it developing into nothing more than a trendy form of garnishing sprinkled into a social media post to make the individual sound informed or progressive. Despite my delight with ethical issues such as ‘consent’ being spotlighted, I also have a deep displeasure towards people or organisations who decorate their policies and statements with this buzzword whilst not taking any tangible steps to implement it.

In this article, I will explore the importance of consent within the context of the Global South– something which, only a few years ago, was considered insignificant by photographers (especially western photographers). In this piece, the people photographed will be referred to as ‘collaborators’ instead of ‘subjects’.

What does this image have to do with medicine in the Global South? Innovex solar technicians like Gertrude are working to improve and stabilize the electrical infrastructure for health centers and hospitals in Uganda and across Africa.

Photo: Nikissi Serumaga / International Trade Center / Fairpicture

To analyse and understand the developments in this present day, we need to go back in time. Charity appeals generally became popular in the 1980s in response to humanitarian issues within the global south, such as the devastating drought in Sudan and Ethiopia. The crisis caused a wave of charities/ International Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) to embark on massive charity campaigns distributed as TV ads, songs and posters e.g World Vision. Its aim was to raise awareness and funds to assist in alleviating the pain of those directly affected by the drought and food shortages. With these campaigns came a swarm of photographers flying into the affected areas and capturing still and moving images of children and adults that embody the catastrophe. Now, it is entirely understandable why there is a need to capture evidence of what’s happening on ground and its impact; however, it becomes problematic when the focus of these campaigns are children – mostly photographed in ways that ‘other’ them (to view or treat a person as different/alien to oneself).

It is still common for photographers to parachute into different parts of the Global South that were or are experiencing humanitarian issues (there has, however, been an increase in local Photographers being hired to tell stories on ground). Their job, in a nutshell, is to appeal to the Global North to donate money to help those affected by humanitarian crises. They achieve this by pulling at the heartstrings of an average human being, which (according to a study posted by UK Fundraising) is usually done by photographing a child affected by the issue. For example, if it is about hunger or sickness, you will get the classic image of a shirtless child with a protruded stomach gazing helplessly into or away from the camera’s lens. These images are guaranteed to move someone in a more privileged position to donate to the cause and thus ‘save’ that child. The issue with this is not necessarily the intention behind it because the intention is usually good. The problem is how these photographs are obtained and eventually distributed.

When discussing medical issues in the Global South, why has it become normalised to use images of children, instead of adult doctors, nurses and medical staff, such as Dr. Chastel N., a paediatrician in the Democratic Republic of Congo?

Photo: Justin Makangara / Swiss TPH / Fairpicture

In most cases, they took these photographs of children without the explicit consent of their guardians (a problem that still arises today but has vastly improved). When a photographer takes a picture of someone, a power exchange happens – the photographer is taking from that specific person. The photographer chooses how collaborators are represented and the narrative pinned on them. When this process happens, especially to a visibly vulnerable minor with vulnerable guardians without their permission, it becomes a massive abuse of power and theft.

‘But what if the guardian gave consent?’ you may ask. Well; it then raises another question: would they have given consent if they were in a more advantageous position? And what kind of consent did they give? Was informed consent-permission given with full knowledge of when, how and for what purpose their image will be used? Did they also understand that they can say ‘no’ or withdraw consent without repercussions? Or was it implied consent - the assumption that the person has accepted being photographed without expressive writing or verbal confirmation? This requires the person to understand that they are being photographed and reacting in a way that confirms their approval, e.g. nodding.

When planning a communication campaign that relies on photos, it is important to analyse the motives for creating certain images and the impact that they might have on those being photographed.

Anne Nwakalor

Despite countless organisations agreeing that consent is important, some, unfortunately, abuse their power by presenting inaccessible consent forms, which means the collaborator will not fully understand what they are filling out. In such cases, consent is weaponised and acts as protection for the organisation - rather than preserving the rights of the collaborator. The essence of a consent form is to protect both parties and clearly state the rights that both parties have regarding the images. It is essential to create structures that ensure those permitting their images to be used are doing so free from deception or complicated legalese language.

Another question to ask yourself is if you were in a part of the Global North with strict rules regarding photographing people, especially minors, would you think it appropriate to photograph a minor, especially without their guardian’s consent? It is imperative to note that just because there may be a variation of laws in some parts of the world, it does not give one the right to exploit situations that would otherwise not present themselves if we were in the Global North.

Photography contains the power to educate

When planning a communication campaign that relies on photos, it is important to analyse the motives for creating certain images and the impact that they might have on those being photographed. Not only must a truthful (a subjective word when it comes to photography) visual depiction of the collaborator be created to avoid misrepresentation, but most importantly, their dignity must be preserved. Text and images that form emotional responses simply through their ability to shock are harmful because it exploits the collaborator’s current situation in order to create sympathy and charitable donations.

I’d like to reiterate that Black and Brown children are not photo props. The same way that you would not take an unsolicited picture of a Caucasian child from the Global North is the same way that it should not be acceptable to photograph children or people within the Global South without their explicit consent. It is indisputable that photography contains the power to educate, inspire, shock and compel its viewers to take action. Pictures evoke strong and public emotions, leading individuals to develop their opinions and conceptions as a response to a visual stimulant. Still, when that visual stimulant begins to convey people in a specific way e.g images that continuously depict Black and Brown children in a monotonous manner, this perpetuated representation becomes the new normal in people's minds, leading individuals to only see Black and Brown children within the context of poverty and suffering.

Latest blog posts

Our community's inspiring voices

July 2024 - Noah Arnold

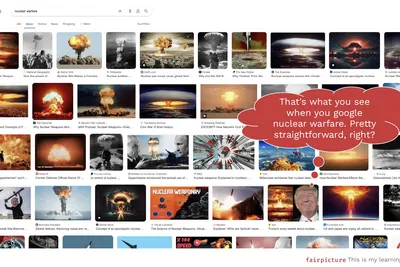

Deconstructing Nuclear Weapons Stereotypes: The Intersection of Journalism and Ethics

The Fairpicture lens on representation and stereotypes is relevant in many fields. See how we challenge the depiction of nuclear weapons, exploring ethical journalism and societal impact.

Learn more about Deconstructing Nuclear Weapons Stereotypes: The Intersection of Journalism and Ethics

May 2024 - N'Deane Helajzen

The Power of Community Storytelling and Co-Creation

Explore the importance of community storytelling and its relationship with co-creation, illustrating how they can enrich collective narratives.

Learn more about The Power of Community Storytelling and Co-Creation

March 2024 - Aurel Vogel

Informed consent: Why an app is better than paper forms

Collecting informed consent for photo and video productions is faster and more secure when using a mobile app instead of paper forms.

Learn more about Informed consent: Why an app is better than paper forms