«Africa» - a majority of the population in the West associate it with hunger, lack of education, high levels of child mortality, and corruption. The continent is perceived as being populated by people who are not able to take care of their problems on their own. Or to put it in common patterns of representation: the progressive, modern, rational, and industrious West creates prosperity. While on the other hand the backward, traditional, emotional, and unproductive South has achieved nothing but poverty since independence from colonial powers. These attributes directly reflect (post)colonial power relations. They discredit the population of entire countries and are a discriminatory daily routine for individuals.

On International Women's Day, 8 March, the women in Lokolo demonstrate for their rights.

DRC 2023: Justin Makangara / Action de Carême/ Fairpicture

We all like pictures. We are always eager to share images. Pictures are great tools to order the world around us and to position ourselves in it: geographically, emotionally, socially - who lives where, under which circumstances, experiencing which joys and hardships. Pictures are more descriptive, more concise, and more expressive than long explanations. «A picture is worth a thousand words» - and when we get to the bottom of something, we «make an impression of it». Pictures are evidence of reality. We learn from pictures and store knowledge with respect to them. Pictures influence the way we interpret how things work in the world. And the more often we see certain images, the more convinced we become that they show exactly what we perceive as "reality". For example, we learn from the wide-reaching campaigns of international aid agencies that people on the African continent mostly live as subsistence farmers. The fact that around 80 percent of the people live in urban areas is ignored in the message the imagery conveys.

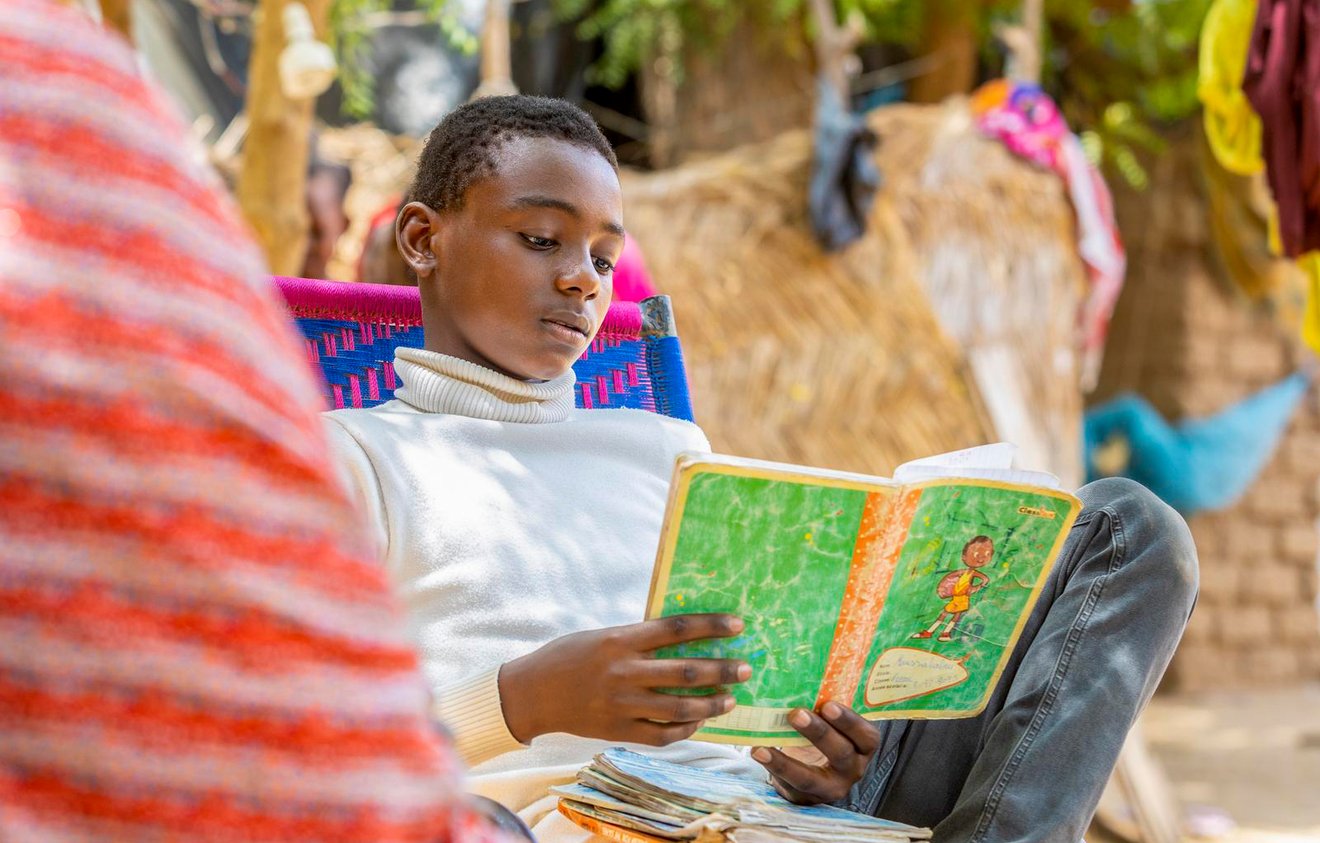

The exploitation of children as cheap labour is a global problem. 15-year-old Moussahabou has worked as a child. Today, like most of his peers, he has the opportunity to attend school.

Niger 2023: Gaïssa Chaïbou Abdoul-Rafik/SOS Villages d'Enfants/Fairpicture

Our world is exceptionally diverse, complex and difficult to understand. Stereotypes are collectively shared attributes that help us simplify this complexity. They form groups of people, attach attributes, and define a person's place in society. Stereotypes are functional because they express a commonly shared understanding of the world in a simple way and form an image in our mind. They help us to assess situations and people more quickly. This includes the fact that we expect certain characteristics and behaviours from people who we see as belonging to specific groups. This is often linked to their gender, skin colour, race, ethnicity, age, educational background, or even with their position in history: as simple labourers, servants, or slaves. Stereotypes direct our attention and make us perceive facts selectively. Depending on the perspective, stereotypes have a positive or negative effect on individuals and whole societies. One source of negative stereotyping was colonialism, which quite strategically relied on stereotypes to legitimise and strengthen unequal power structures.

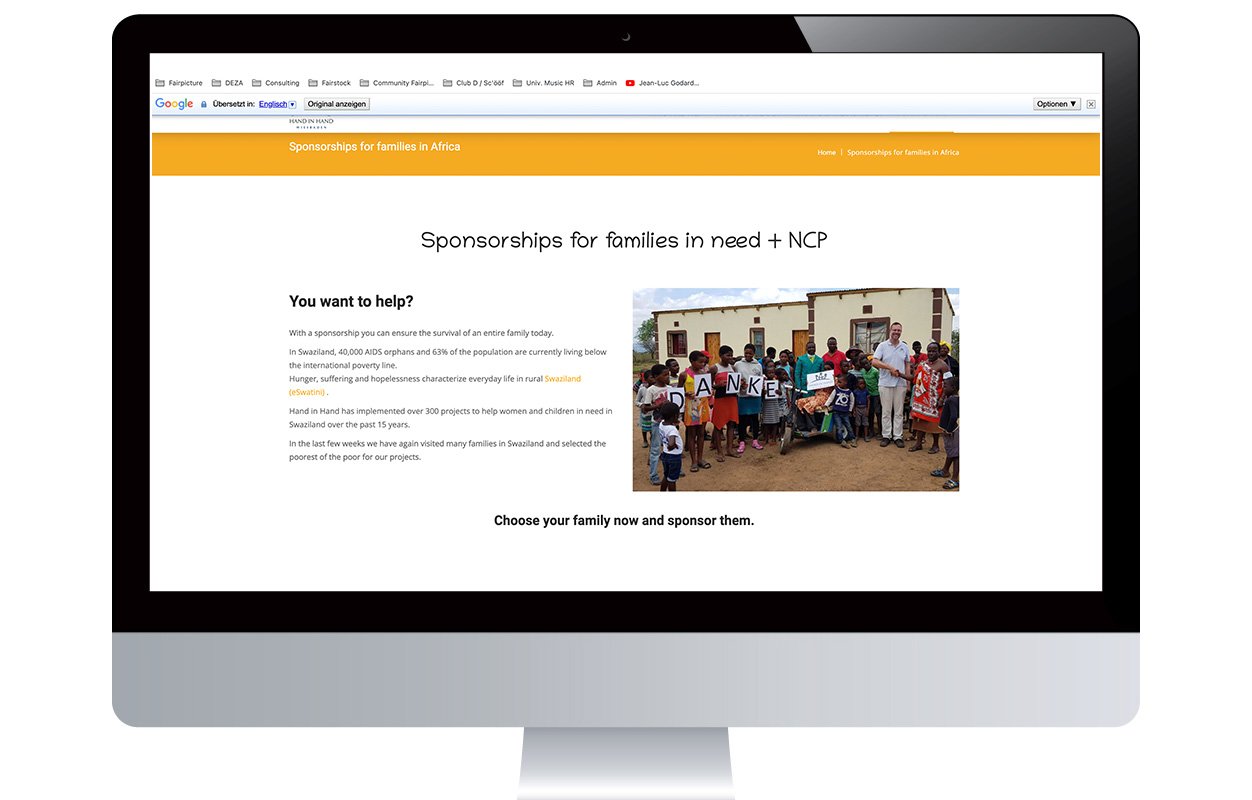

Such images, long thought to have been overcome, are still prevalent in the communication of international aid organisations.

Source 26 June 2023: https://handinhand-ev.org/patenschaften/ Screenshot.

White supremacy and the notion of a racial hierarchy are constitutive elements of the colonial past. The patronising care for the poor is one problematic manifestation in this context. Despite having been criticised for decades, representations sustaining inequality have lost little of their power in visual communication. White aid workers and experts stand as guarantors of aid effectiveness. On captions, white people carry names, black people do not. «Beneficiaries'» (i.e. people who are in the favour of white helpers) laugh and show their gratitude for the help they have received. The messages underlying such stereotypes work. At the same time, they marginalise, they legitimise, reinforce, and naturalise structural inequality. They degrade people and turn them into illustrations and objects of the donation market. They hurt because they create second and third classes of people.

Jörg Arnold | Fairpicture

The impact of images that reproduce colonial power relations is dramatic. For example, it directly influences how Europe shapes its refugee policy. How much value is placed on people trying to reach Europe and cross the Mediterranean in an overcrowded boat?

If one takes the decolonisation of visual communication seriously, then it is not enough to simply exchange the images. It is right, but not sufficient, to replace «poverty porn» with imagery that shows «solutions». We need to focus on more than preserving the dignity of the people photographed or filmed, as many organisational Code of Conducts advise. If you really want to deal with the decolonisation of the visual, you have to ask the question of «how».

The decolonisation of (visual) communication cannot be facilitated quickly. But it is not a question of whether such a process is necessary or not. It is only a question of how soon an organisation wants to start it. Let me answer the above questions with concrete recommendations for action. They make first steps possible:

November 2025 - Prof. Dr. Peter G. Kirchschlaeger

This article explores what truly makes a picture “ethical” in the age of AI-generated imagery, arguing for human-made, consent-based visuals that respect truth, dignity and autonomy.

Learn more about Ethical Pictures in the Age of AI – An Opinion Piece

November 2025 - Arwa Elabasy

Discover how transparent communication and ethical storytelling can help NGOs and non-profits build trust, foster inclusion, and challenge traditional narratives.

Learn more about Truth in the Age of Machines: Why Ethical Communication Is Humanity’s Last Campaign

October 2025 - David Girling

Interviews with storytellers from Cambodia, Burundi and Kenya show how NGOs can turn ethical guidelines into practice—centering consent, dignity and context.

Learn more about The Practicalities of Ethical Guidelines in NGO Storytelling