How to talk about consent and Misery Porn?

by

Jaìr F. Coll, April 2023

by

Jaìr F. Coll, April 2023

The term ‘Misery porn’ was coined 40 years ago to parody the documentary filmmakers who commercialized Colombia's misery. The concept still persists, while wavering.

A journalist interviews a couple, a man and a woman, with their young children in front of a house made of old wood, bamboo poles and a tin roof. The “documentary” filmmakers not only paid them to pretend to be the owners of the home, but also to answer a script with questions such as "Do you know how to read and write?" "Are your children vaccinated against smallpox?" "Do you plan to have more children?" After the interviewer begins an elaborate speech about misery in Colombia, another man — the real owner of the house — steps in front of the camera, interrupting filming.

"You greedy people!,” the man complains to the filmmakers. The producer tries to bribe him so they can finish the film, but the homeowner replies: "Do you know what you can do with this money?" He pulls down his pants, wipes his back with the bills, and then scares off the entire crew with a machete, destroying one of the rolls of film and saying: "Cut." There is silence, and he asks the camera: "Did you get it?”

Everything the viewer saw was a lie. A parody, a mockumentary. The title of the short film is 'Agarrando pueblo' ('Vampires of Misery'), directed by Colombians Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo in the city of Cali. With this piece, both wanted to denounce how there were documentary filmmakers in the 1970s who turned the country's distress or poverty into merchandise, which they sold abroad. Ospina and Mayolo called these attitudes “misery porn.”

40 years after the film’s release and the term has not ceased to be in use. Now, it is part of the common vocabulary for every documentary filmmaker, photographer or journalist in Latin America. Some use it to accuse unethical situations in their peer’s work, especially when there is a lack of consent from the person portrayed or a fictitious “consent” exists by way of an economic transaction. In both cases: the person is reduced to their condition of misery, stripping them of the rest of their humanity.

"It is an enunciation that is made superficially because these vulnerable people appear as worthy of pity and attention, but a victim is not only a victim. He or she is also someone with a symbolic and cultural world," says Pedro Adrián Zuluaga, writer and film critic.

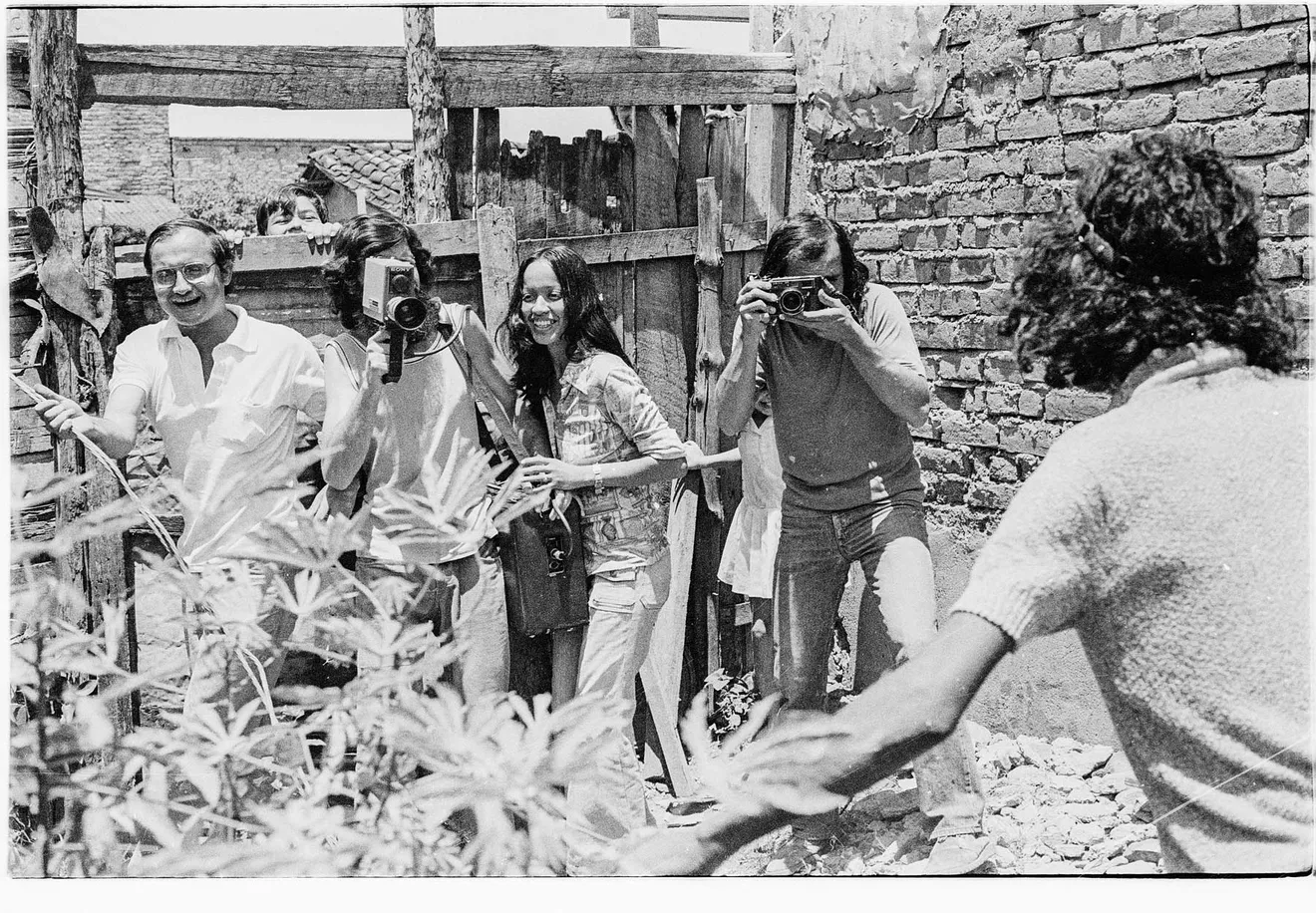

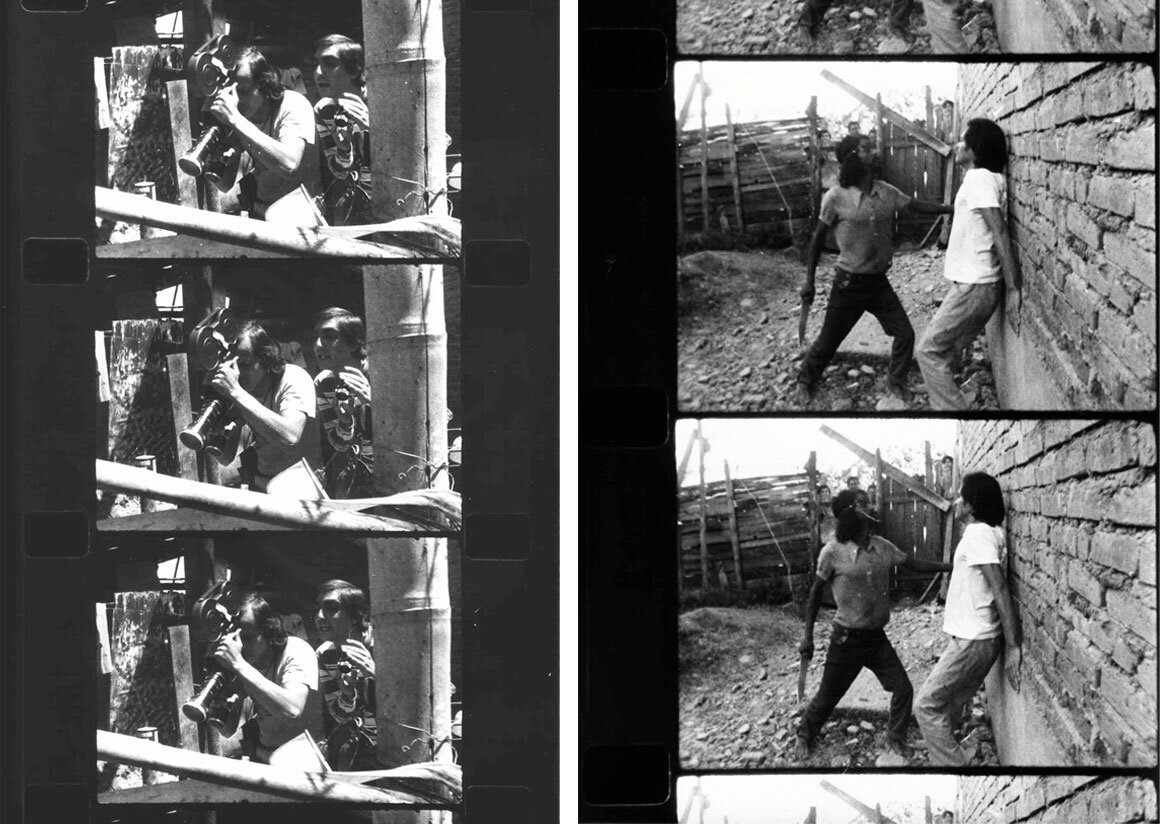

'Agarrando Pueblo' or Vampires of Misery (1977), by Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo.

In addition, misery is not only poverty. It is a condition that causes a person's lack of dignity, so the reading goes beyond economic hardship. This is an opinion shared by Christian Escobar Mora, a photojournalist who has covered the Colombian armed conflict since 2002 for international agencies and media. For him, misery porn depends on a porn aesthetic.

EscobarMora explains: "It is a direct fascination with human misery. That is why the color of yellow journalism (sensationalism) is created by the one who documents it, but undoubtedly by the one who receives it as well." This not only refers to the media, but also to the reader, who can have harmful intentions with an image, twisting it for other's purposes.

"To give you an example, photographs that I have taken of combats between the Colombian guerrilla and the Army have been used years later to assure that those guerrilla members were indigenous people who participated in government processes. These are false and uninformed assertions and, therefore, there has been a porn aesthetic, because the reason for being of these people is ignored and my photos are used to create a political conditioning", recalls the photojournalist.

When Ospina and Mayolo premiered their mockumentary in 1977, they read a manifesto explaining what misery porn was - a document barely two-thirds of a page long. Analyses have expanded the definition and implications of the famous term, with more than 6600 articles published in Google Scholar and hundreds of comments and discussions on social networks.

There is no freedom of interpretation to tell a story

Juanita Escobar, documentary photographer, adds that misery porn also manifests itself in other scenarios entirely different from those raised in the film. This includes some NGOs’ towards human tragedy, when despair must comply with certain factors that "are enough" to access their subsidies.

"They are organizations that have boxes and squares of a form of how the world works, of how the vulnerable populations they want to support are. That is why when they send photographers to confirm those preconceived ideas - to check those boxes. In other words, there is no freedom of interpretation to tell a story. There is no need to look for the Guinness Record for the Saddest Story," Escobar explains.

For the documentary photographer, understanding what is behind the word ‘consent’ is key to avoid such approaches: "It is a relationship that is formed over time and through an agreement that allows the exchange of information on both sides, without imposing my personal vision on the other.”

'Agarrando Pueblo' or Vampires of Misery (1977), by Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo.

What is the cure?

Filmmaker Óscar Ruiz Navia likes to refer back to the words of director Luis Ospina to understand the difference between a newscast and a documentary. "In the former, the journalist sets the time; with the latter, the subject.” Although there are cases of deep and responsible reporting, Ruiz Navia wants to stress the importance of a calm and respectful approach to the person or situation being documented before starting a production.

"Misery porn has to do with the ‘how’, not the ‘what’ (i.e. the misery itself). A ‘how’ that stole the spirit of the real. What 'Agarrando Pueblo' teaches us is the importance of the time one spends with the subject to achieve more depth, as well as distance. It is not the same to look at reality with a wide-angle lens or a telephoto lens, just to give an example," the filmmaker points out.

Although the documentary filmmakers who are parodied in the short film had (apparently) intentions to contribute socially and politically, this mattered little in the face of their disrespectful representation of misery. Paradoxically, it was these very situations that opened the eyes of a new generation of image creators.

"Misery porn is a discourse that was exploited and exhausted so much that it was awarded abroad. That hurt us a great deal, and we realized it had to stop. The message of the film is to see the vulnerable person as a subject and not as an object," says Vilena Figueira, expert and scholar at the latin american photographic archive.

'Agarrando Pueblo' or Vampires of Misery (1977), by Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo.

There is no need to look for the Guinness Record for the Saddest Story!

Juanita Escobar, Documentary Photographer

The superficial discourse of porn-misery

Although 'Agarrando Pueblo' talks about the 'how' but not the 'what', there are also misreadings that believe that misery porn already exists when a vulnerable situation is documented. This ignores not only the message of the mockumentary, which features actors from impoverished communities themselves, but also much of the filmography of Ospina and Mayolo, who worked extensively with such populations for many years.

Anthropologist and photographer Jorge Panchoaga believes that in addition to the fact that misery porn can reduce the ability to analyse a work from a single focus, it also cannot be the guide to ethics and consent.

"Feminism has changed many ethical things that before seemed normal. So have decolonial and anti-racist approaches. To think that misery porn is the key to understanding all these cultural and ethical social movements is to believe too much in the concept," he stresses.

The consequences can be worse, since the term is sometimes used as a tool to censor and create inaccurate interpretations about a reality. A mistaken reading can lead us to believe that certain social issues are not worthy of being documented.

The photojournalist EscobarMora states: "There is no real reason for not showing that reality, far from personal or unconscious intentions that are tied to a religion, government, institution, etc. Not showing is also an absence of values.”

Selected blog posts

July 2023 - Daniel Caspari

From visual to ethical storytelling

Introduction on the core elements of visual and ethical communication on the basis of case studies Fairpicture accompanied during the last month.

Learn more about From visual to ethical storytelling

January 2022 - Aurel Vogel

Update #8: Connecting the dots

Progress has a strange pace. Months pass without noteworthy changes and suddenly everything comes together. Last year Fairpicture pretty much followed this pattern. So let’s look backwards and connect the dots.

Learn more about Update #8: Connecting the dots

July 2024 - Noah Arnold

Deconstructing Nuclear Weapons Stereotypes: The Intersection of Journalism and Ethics

The Fairpicture lens on representation and stereotypes is relevant in many fields. See how we challenge the depiction of nuclear weapons, exploring ethical journalism and societal impact.

Learn more about Deconstructing Nuclear Weapons Stereotypes: The Intersection of Journalism and Ethics