Who doesn’t know the shyness of photographing strangers in their everyday lives. For example the fishwives at the market in Chisinau, Moldova, selling their live carp. Or the grandmother in Lobalong, South Sudan, smoking her pipe with pleasure. And then it is us with our camera. We feel that we are crossing a line when we point our lens at the picturesque subjects and press the shutter.

On the other hand: Who doesn’t know the annoyance of being recognised as a local and photographed without being asked by some tourist on the street or at the market? And who doesn’t know the shame of looking at a picture that shows oneself? When the hair is in the wrong position, the nose is too big, the shirt is fitting badly.

Photo: Sandra Sebastian/Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe/Fairpicture

“I don’t want you to take my picture.”—The denunciation of a hitherto unquestionable consent may be hard to digest for the father of a pubescent daughter. But it is the honest expression of what the “right to one’s own image” means. Legally, it is a narrower or broader personal right. A right that can be sued for. In Germany, for example, “anyone who unauthorisedly produces or transmits a picture that shows the helplessness of another person and thereby violates the highly personal sphere of life of the person depicted is liable to a prison sentence of up to two years.”

Jörg Arnold

Fairpicture

21 January 2021: The family of Arben Mustafa (39) and Sevdije Mustafa (40) in Prizren, Kosovo. Their 13-year-old daughter Xhulieta attends Concordia Tranzit's music school.

Photo: Samir Karahoda/Concordia/Fairpicture

But where there is no plaintiff, there is no judge. And the greater the physical and social distance, the less the rights and personal integrity of the people depicted count. Earthquake victims find themselves unawares as illustrators of stories that do not correspond to the realities of their lives, provided with statements that they never made in this way. “Do No Harm”, “Human Rights-Based Approach”—principles that apply to the programme work of development organisations and to the actions of multinational corporations must also apply to fundraising and communication: People who are willing to make their face, their person and their life situation public are not paid models who sell themselves to advertising. These people have rights they do not have to ask for. They decide how much of themselves they want to reveal and whether the Sunday shirt fits their poverty.

Swiss Data Protection Commissioner

Rights are not just protections. They also define entitlements. The Swiss Data Protection Commissioner, for example, has a clear opinion on what this means in relation to the “right to one’s own image”. Namely, “the people depicted usually decide whether and in what form an image may be taken and published. For this reason, photos may usually only be published if those depicted in them have given their consent.”

Obtaining informed consent is not just an annoying formality that can be done on the side. It is about explaining the context to the people depicted, informing them of what will happen to their images and telling them that they do not have to make themselves available if they do not want to. This is a challenging task for the photographers and video journalists. They need not only social skills for it, but also time—time that has to be made available to them by the clients and that is paid for.

23 August 2020. Nurul Amin's daughter Mubarika stands in front of the door and looks outside. She says: “Our school is closed. We have to stay inside all day. We can't go outside to play because of the virus.”

Photo: Mohammad Rakibul Hasan/Danish Refugee Council/Fairpicture

War, disaster events: There are few situations in which obtaining informed consent is not possible. And the excuse that those photographed have no idea what happens to their picture anyway is just as discriminatory and belittling as the attitude that the willingness to be photographed is something like a quid pro quo for help rendered. It is not about knowledge and gratitude, but about respect, fairness and justice. There is no reason not to ask someone if he or she may be photographed or filmed (for example with the FairConsent app). And there is no reason to assume any kind of consent. It is time to leave this remnant of the colonial past behind.

January 2021 - Pia Zanetti

Pia Zanetti explains her view on the role and responsibility of Fairpicture as an interest broker between photographers, clients and the public.

Learn more about Fairpicture as an interest broker between photographers and clients

March 2023 - Miša Krenčeyová

The images that come into your mind when you think of the term “Third World”, will most probably be related to this symbolic figure - through language.

Learn more about In social justice, internal language guidelines are never “done”

November 2025 - Prof. Dr. Peter G. Kirchschlaeger

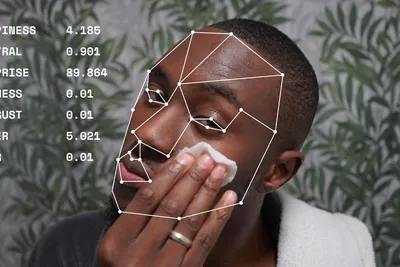

This article explores what truly makes a picture “ethical” in the age of AI-generated imagery, arguing for human-made, consent-based visuals that respect truth, dignity and autonomy.

Learn more about Ethical Pictures in the Age of AI – An Opinion Piece