When you think of the term “Third World”, what kind of images come into your mind? How do these images make you feel?

My assumption is that your visual and emotional associations to “Third World” will largely depend on whether you are located within or outside of spaces the term supposedly refers to. Sure, your ideas will be affected by what you know or don’t know about the history of the term and how familiar you are with current debates around political terminology in the global context. But your reaction will, most of all, depend on how the term speaks to you, how it addresses you, what it invites you to be. A saviour or a victim? A liberation fighter? An ally? The images that come into your mind will most probably be related to this symbolic figure - through language.

The Mkhize family, who currently reside in Mzimhlophe, Soweto, are pictured at home. The family receives financial assistance and support from the Sophiatown Community Psychological Services(SCPS).

Picture: Mpumelelo Buthelezi / Solidarmed / Fairpicture

In the context of Fairpicture’s work, it might seem counterintuitive to focus on terminology where we are focused on visual communication. But when speaking about visuals, we do - of course - rely on verbal language, be it in meetings, briefs, or publications. We communicate with stakeholders and partners in diverse national, cultural, professional, and organisational contexts. These individuals and organisations might rely on different terms to refer to the same things or use the same term to express different ideas. This will depend on their linguistic habits, preferences, and expectations. At Fairpicture, we want to take into account these different contexts and perspectives, while still being guided by our values . This resulted in our consulting and content marketing circles developing language guidelines that allow our organisation to consciously select appropriate terminology in line with the principles that guide our work in the visual sphere.

Having internal language guidelines is a widespread practice of many organisations, whether that be non-profits or corporations. It helps us establish meaning for crucial concepts and unify our communications, often including glossaries that can be quickly consulted in daily operations. As helpful as this may be, those aspiring to contribute to social and global justice are not well served by clinging to static definitions. Why? The usage of language is the result of negotiation processes in the context of power relations. Looking for the most appropriate terms requires constant awareness of how contexts and debates about issues are changing. At the same time, the connotation of terms stems from wider historical and political factors. Over decades, a term changes its meaning, it might catch on to denote a particular idea, but over time, it gets loaded with new connotations and is replaced by another term. In this sense, a quick-fix glossary cannot ever be “finished”. It is always a work in progress.

This process requires reconciling contradictions. One example relates to the term “Global South”. We use it instead of the term “Third World”. In 2023, the former does not come with the same problematic baggage as the latter. In current Western discourses, “Third World” carries derogatory connotations of presumed “backwardness”, while “Global South” points to global relations of inequality: the qualifier “global” pushes the term over from geography into politics - not all places located in the “Global South” are on the Southern Hemisphere. In a global context, societies, groups, individuals located in the “Global South” are those holding positions of structurally less power than those located in the “Global North”. This terminology allows us to name relations of exploitation and oppression instead of focusing on simplistic notions of presumed “difference”. Difference is relevant, but in a way very different from what the connotations of “Third World” in the West suggest: it is differences in power that are crucial.

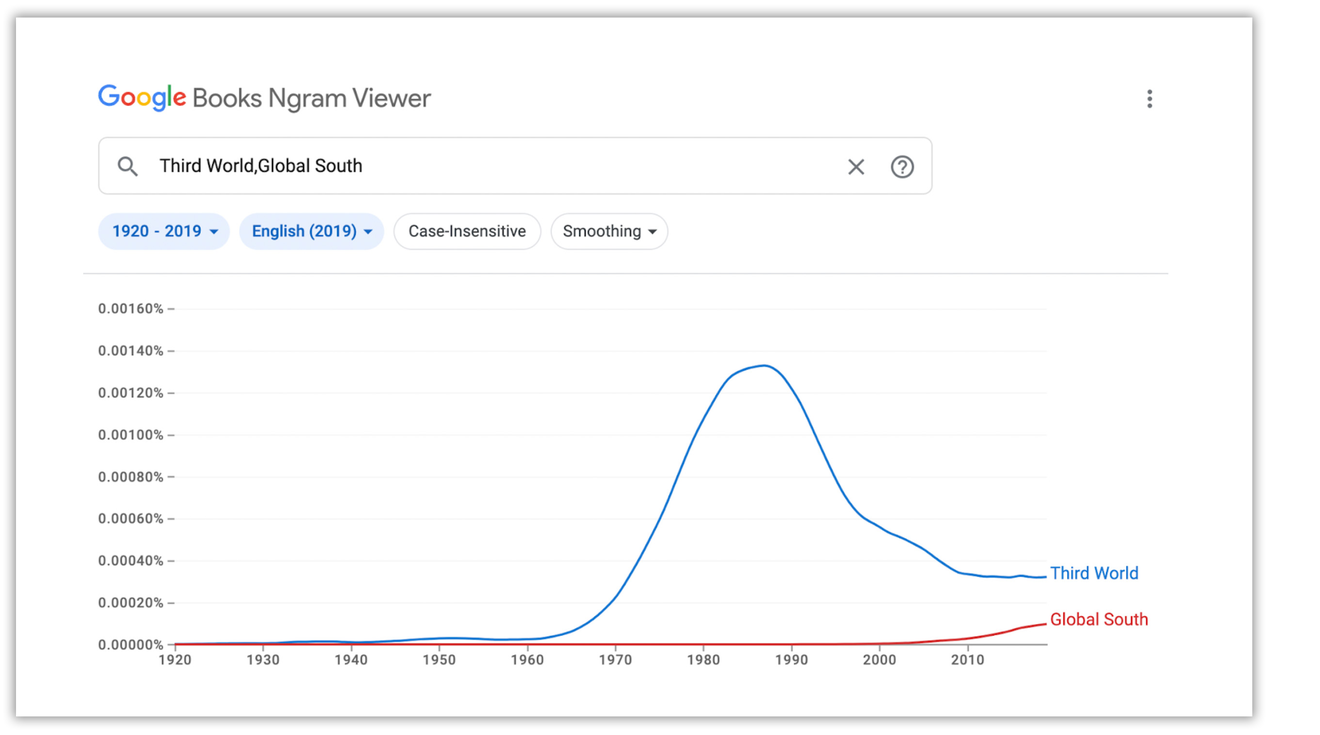

Screenshot of Google Books Ngram Viewer, https://books.google.com/ngrams/.

The Google Books Ngram Viewer visualises how often a term is mentioned over time in the corpus of Google Books. The above graph illustrates that references to the “Third World” increased throughout the 1960s, peaked in the 1980s and started declining in the 1990s, after the end of the Cold War. The curve for “Global South” has grown only recently, since the 2000s.

Somewhat ironically, it is the history of the concept of the “Third World” that so strongly articulates the need for changing global power relations. It dates back to the 1950s and initially referred to African and Asian countries that rejected the Cold War logic, collectively demanded self-determination in the context of decolonisation, and formed the so-called Non-Aligned Movement. The “three worlds” of the Cold War era referred to political and ideological alliances and affiliations: capitalist (“First World”), communist (“Second World”) and neutral (“Third World”).

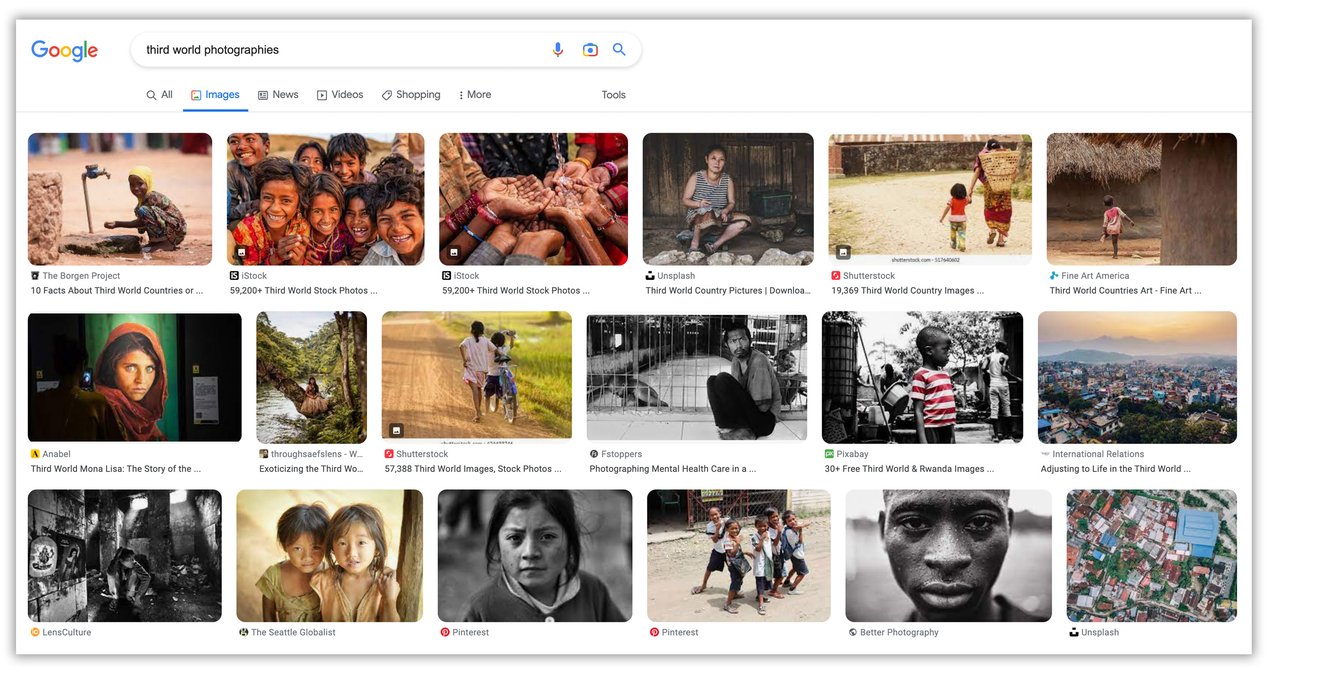

In political and academic discourses, the “Third World” then stood for explicitly emancipatory and radical positions that challenged global inequalities and Western domination. With the end of the Cold War, the concept abruptly became old-fashioned in the 1990s. While the term remained part of popular vocabulary also in the West, it was continuously stripped of its political character and increasingly loaded with stereotypical content. Enter “Third World” into any image search platform and what you get are stereotypical images of poverty and deprivation.

Screenshot of the first page of Google Image Search results for ‘“Third world” photographs’, search location Bern/Switzerland on March 29th, 2023.

Is this different when it comes to the concept of the “Global South”? Not necessarily. The latter is contested as well. After all, the more you lean into the history and diverse meanings of any term, the more contradictions you find. “Global South”, too, can be used to homogenise and essentialise communities, countries, or whole continents and lock them in stereotypes of suffering and destitution. It, too, can serve to conceal the heterogeneity of interests and differences within societies. Yet it does include that important reference to the global dimension and thus helps to name particular patterns of inequality. Contrary to terms such as “developing country” or “emerging market”, the “Global South” does not invoke only one predominant connotation. Its ambiguity carries with it a certain irritation and allows for challenging stereotypical representations.

Locating the different stakeholders that work with Fairpicture globally, therefore, we still rely on the distinction between the “Global South” and the “Global North”. Doing so is a conscious choice for handling contradictions and mirrors the “work in progress” regarding our language use that I referred to above. Our internal language guidelines, then, are the result of reflections such as the ones in this blog post.

We use certain terms because they are accessible to a wider audience and established as the “state of the art” in current debates about global inequalities and power relations. We use them not because they would necessarily always mean exactly what we want them to, but rather because they do the least possible harm. They allow us to position ourselves in particular discourses or to communicate our messages to specific target groups.

Miša Krenčeyová, Fairpicture

Our language guidelines include terms to use depending on context. Have you ever heard of the concept of “Majority World”, for example? Coined by Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam, it refers to the fact that people belonging to contexts called “developing” or “Third World” are, well, exactly that: the majority of the world’s population. The concept allows us to break with dominant notions of “development” by appealing to a totally different logic. Whether it is understandable, however, depends on the audience's familiarity with it or, alternatively, the time and space that can be allocated to explaining it and discussing it with those for whom it is new or irritating. This is part of the context that our language guidelines invoke.

These guidelines, then, are an invitation to select appropriate terms in response to context and intention on the basis of a critical questioning of language choice: Does this term really express what I want it to say? Can I use an alternative term that does not carry the connotations that I want to avoid? Am I actually referring to a specific issue where a completely different term might be more useful?

If you substitute “term” for “photo” in the above questions, you instantly can see why we speak about language even though visuals are at the centre of our work at Fairpicture. Both words and images are symbols that point to wider contexts without our intentions. Selecting the most appropriate term - or image - for a given context means making a conscious choice amidst contradictions, without expecting this choice to be forever valid. Uttering a particular term comes with the commitment to let go of that term once we found a better alternative - and with the invitation for dialogue with others committed to the same cause: ethical communication.

November 2025 - Prof. Dr. Peter G. Kirchschlaeger

This article explores what truly makes a picture “ethical” in the age of AI-generated imagery, arguing for human-made, consent-based visuals that respect truth, dignity and autonomy.

Learn more about Ethical Pictures in the Age of AI – An Opinion Piece

November 2025 - Arwa Elabasy

Discover how transparent communication and ethical storytelling can help NGOs and non-profits build trust, foster inclusion, and challenge traditional narratives.

Learn more about Truth in the Age of Machines: Why Ethical Communication Is Humanity’s Last Campaign

October 2025 - David Girling

Interviews with storytellers from Cambodia, Burundi and Kenya show how NGOs can turn ethical guidelines into practice—centering consent, dignity and context.

Learn more about The Practicalities of Ethical Guidelines in NGO Storytelling