©Tendai Marima

Clack, clack, clack. That’s the sound of a bursting shutter in the wild. The small birds at the water holes fly away at the first burst of clicks and the elephants pause cautiously, probably wondering if the clacking sound is a potential threat. Going on a five-day safari at Hwange National Park in north western Zimbabwe taught me more about patience and presence in photography than I could have ever anticipated.

Creator

Tendai Marima

Location

Zimbabwe

Date

Nov. 4, 2021

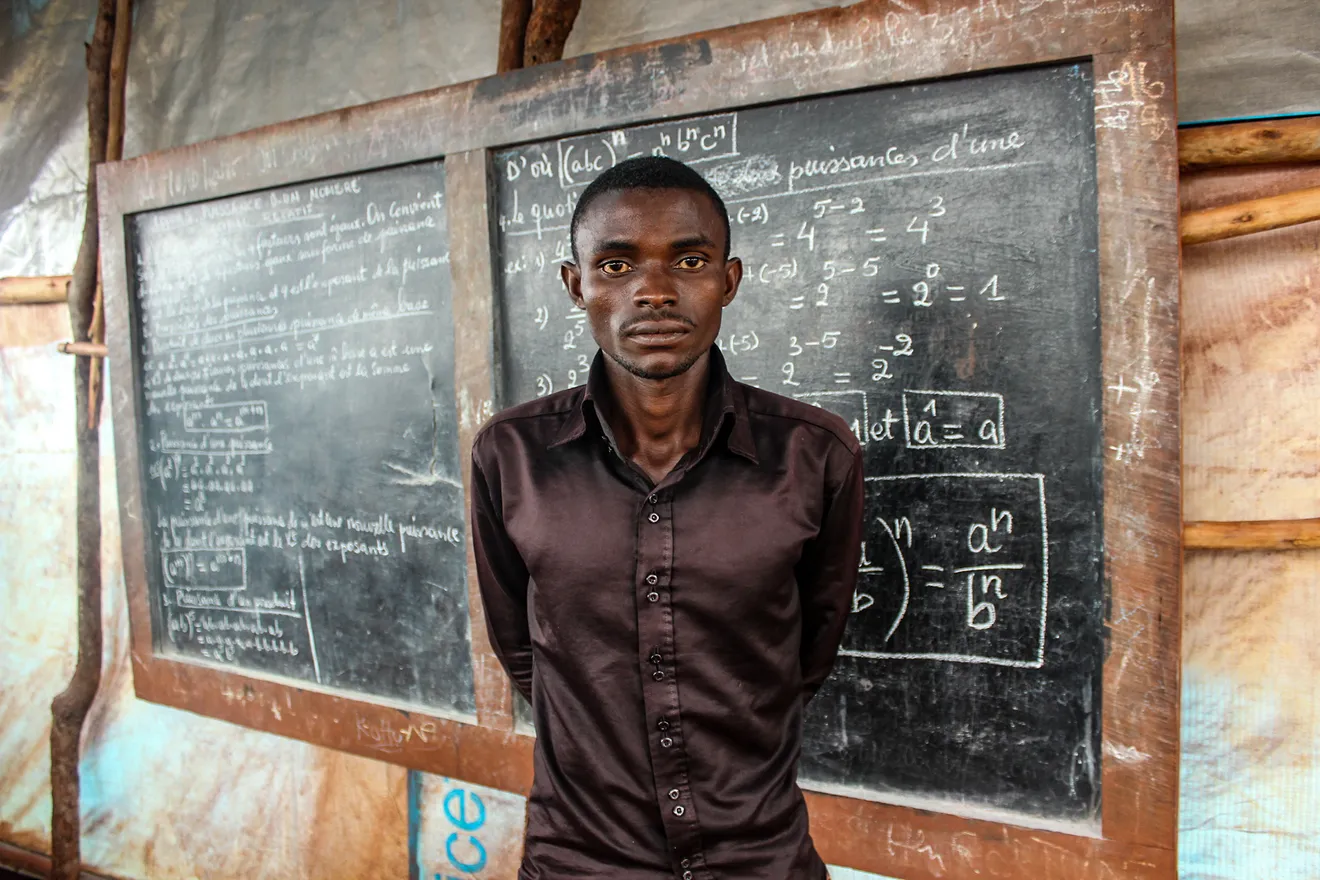

John Posco, 27, a Burundian second year university student, had to drop out of school when a political crisis in 2015 forced thousands of Burundians to flee to neighbouring Tanzania. At Nyarugusu Camp in Tanzania, one of Africa’s largest refugee camps, he teaches refugee children.

Being relatable is important in documentary photography and I was able to photograph Posco after we’d talked about university, and he wanted to be seen beyond his life as a refugee.

©Tendai Marima

I took it for granted that I was on a photo safari trip with friends and didn’t realize that this particular experience was intense and very different. Indeed there’s a difference between being a wildlife photographer and a photojournalist out in the wild. It took time to understand that this time, me and my camera were the strangers in this habitat and I was the one who needed to blend in.

My photographer friends were selective in what they captured and they had cameras with the silent shutter option. This made me think they had a special privilege, but honestly, that wasn’t true and the debates about the economics of photography really don’t matter in the bush. Silence is how not to impose one’s presence, it’s much the same as the practice of documentary photography. The photographer has to immerse themselves into the community.

Tendai Marima

A good storyteller knows how to do this by observing behaviour and building relationships with the photographed. To impose presence or preconceived ideas can easily lead to the photographer becoming an unwelcome stranger, regardless of how important his assignment is.

©Tendai Marima

Often, engagement with a subject is the most essential tool to getting a good photograph, but on the first days I spent a lot of time shooting. Pressing the shutter can get so addictive that there’s not much time to think about what you’re shooting or where the actual picture in what you’re clicking on is. The aim of shooting is not to get a repetitive generic picture of an animal, but to get quality images that are unique from others and that show that I’ve spent some time trying to learn about animal behaviour.

Peggy Masuku, two-time winner of the My Beautiful Home Competition, holds a calabash inside her decorated kitchen hut in Mafela Village, Matobo, Zimbabwe. The contest celebrates the art of painting the home using traditional patterns and natural paints.

In documentary work, when people tell their own stories without needing prompts it makes the work much easier and Masuku is one of those people. We met in a peculiar way, but she was very warm and easy to talk to.

©Tendai Marima

To get those quality images, I need to spend more time in the bush to get to know an animal’s behaviour and to anticipate their next movement without being so scared. Elephants, for example, don’t just spring at people because they feel like it. Instead, they are sensitive and scared of humans. That’s why they raise their trunks into the air first before venturing towards the water. They are wary of us because of poaching. Perhaps in a similar way, in documentaries, when being in a new community, people are also nervous and first need to learn that one is not a threat before they can trust and allow the stranger to photograph them.

Tendai Marima

©Tendai Marima

The job of the photographer is to be a witness, to observe and document. This safari trip taught me how not to impose myself because although I’m an observer I can also be an invader. In documentary work, I’m the one who imposes myself on others because I’m the ‘new presence’ in someone’s everyday life. So I need to be more confident and aware of what my imposed presence does to others. Even with consent and familiarity, ethical questions remain; does the appearance of a camera make people guarded or more performative knowing that their life is being captured in a moment?

An elderly woman, Mavis Dube, at the Richmond Landfill Site in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe carries a sack that she'll fill up with opaque bottles for recycling.

©Tendai Marima

Wildlife photography is an intuitive craft; you learn to be quiet and to take the time to anticipate. But this is another lesson I learnt the hard way: you don’t always get the picture you search for. At first it was fun to search for lions since they’re not easy to find and roam with their chosen pride. Hearing them roar through the night was scary, but exhilarating! Although a lion’s roar can be heard as far as 8 km away, I couldn’t help but think they were very close and a sighting was a real possibility. Seeing fresh tracks the next morning made the search for the big cats even more exciting, but day after day we’d see nothing but paw prints in the sand and miles of dry grass and thorn trees. On one occasion a non-photographer spotted lionesses in the distance but they walked into the grass before anyone else could see them.

Drone searches and meticulous scanning through binoculars and long lenses yielded nothing. The lionesses had found their cover in the brown grass and weren’t interested in giving us humans a sunset show. At this point, I finally gave up on the lions; three days of fixating on what I wanted to see meant I wasn’t fully appreciating the variety of wildlife I was actually seeing and capturing.

Spotting a pair of large hyenas at 3 a.m. more than made up for the lions. Although I was very sleepy and without my camera in hand, it was great to discover the rustling noise which had scared away a herd of elephants earlier. Older spotted hyenas are not seen so easily in this wildlife park. It’s often the young ones prancing about on the dust roads or cackling in the bushes, so this was a rare sighting.

I don’t regret not photographing them. What would I shoot in such darkness anyway. And besides, some images are best kept as nature’s secrets. I’m yet to face a similar dilemma with documentary photography. Often, I don’t push for a picture because my instincts tell me I need to get to know people better before I tell their story so I’m prepared to return to a place.

Tendai Marima

In nature it’s a little different because the pictures are everywhere, but you won’t see them if the picture in your mind is all you want to see. That’s the danger of having a preconceived picture, which is the same in documentary practice.

That’s why staged pictures often fail. When humans are the central character in a picture, you can’t coax them into emotions. However, there are many interesting expressions that can convey an experience. Sometimes with the setup shot, an image is found after many trial and error shots – but often it’s the candid and unexpected moments that bring out the image.

One can’t predict how a photo project will turn out and I’m learning in many ways that I must allow stories to evolve. I’ll return to the savannah bush soon and I know each time I go back afterwards, I’ll see it through wildly different eyes.

April 2021 - Fairtrade Germany

Impact diaries is the word of the hour. Check out this inspiring and fresh approach to campaigning and learn how farmers tell their own stories… with a smartphone!

Learn more about Very fair, indeed!

May 2022 - Grundfos Foundation

The Palgarh district is one of the driest terrains in India. Fairpicture photographer Avijit Ghosh documented the installation of water pumps and got fascinated on how it’s changing people’s lives.

Learn more about The veins of water

June 2023 - Solidar Suisse

Authentic photos which reflect the work of a humanitarian aid organisation and preserve the dignity of the people.

Learn more about Depicting displaced people with dignity